Battery Design & Assembly

Battery Design & Assembly

Insulation Guide: Fishpaper, Kapton, and Short Prevention

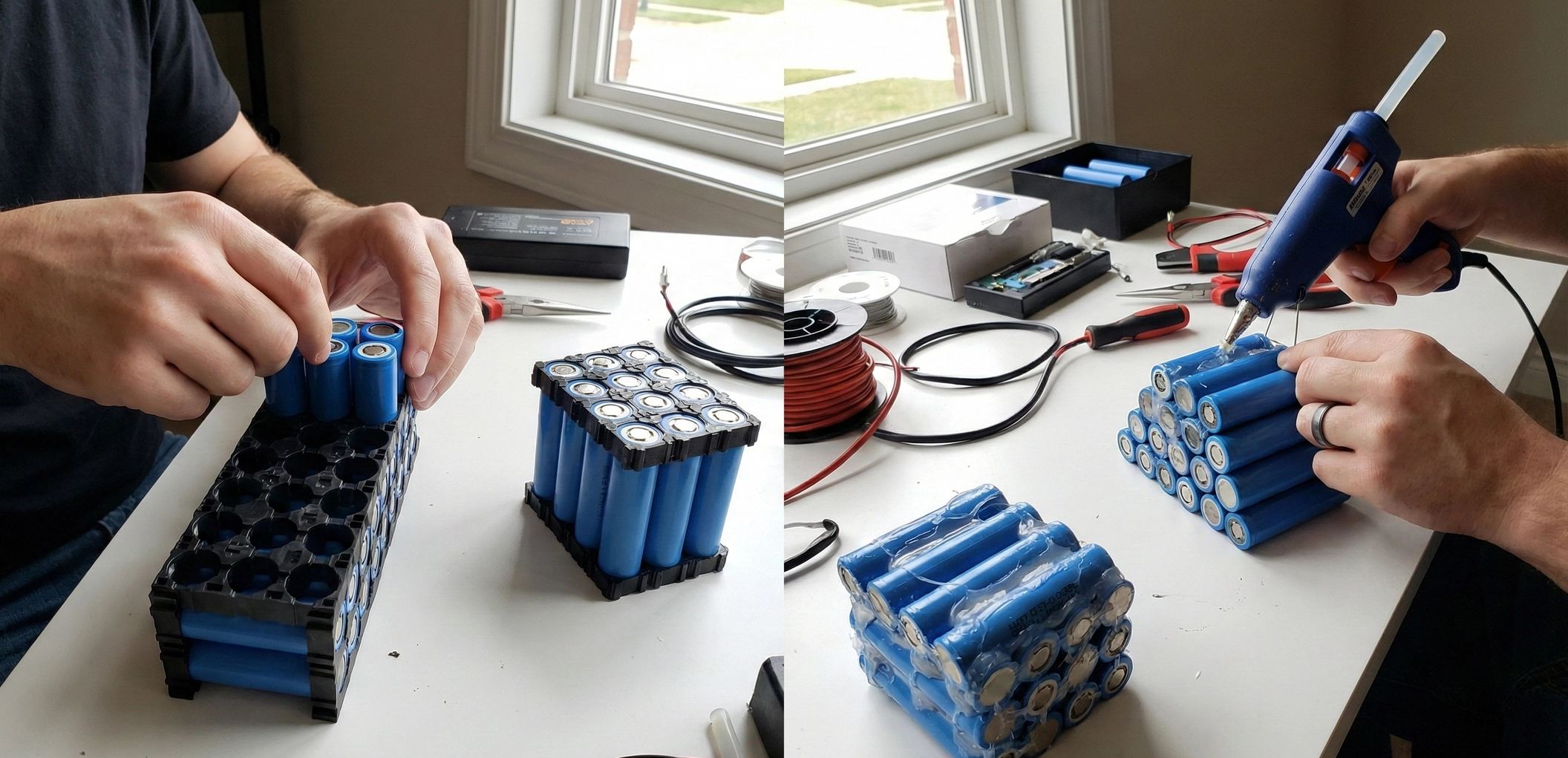

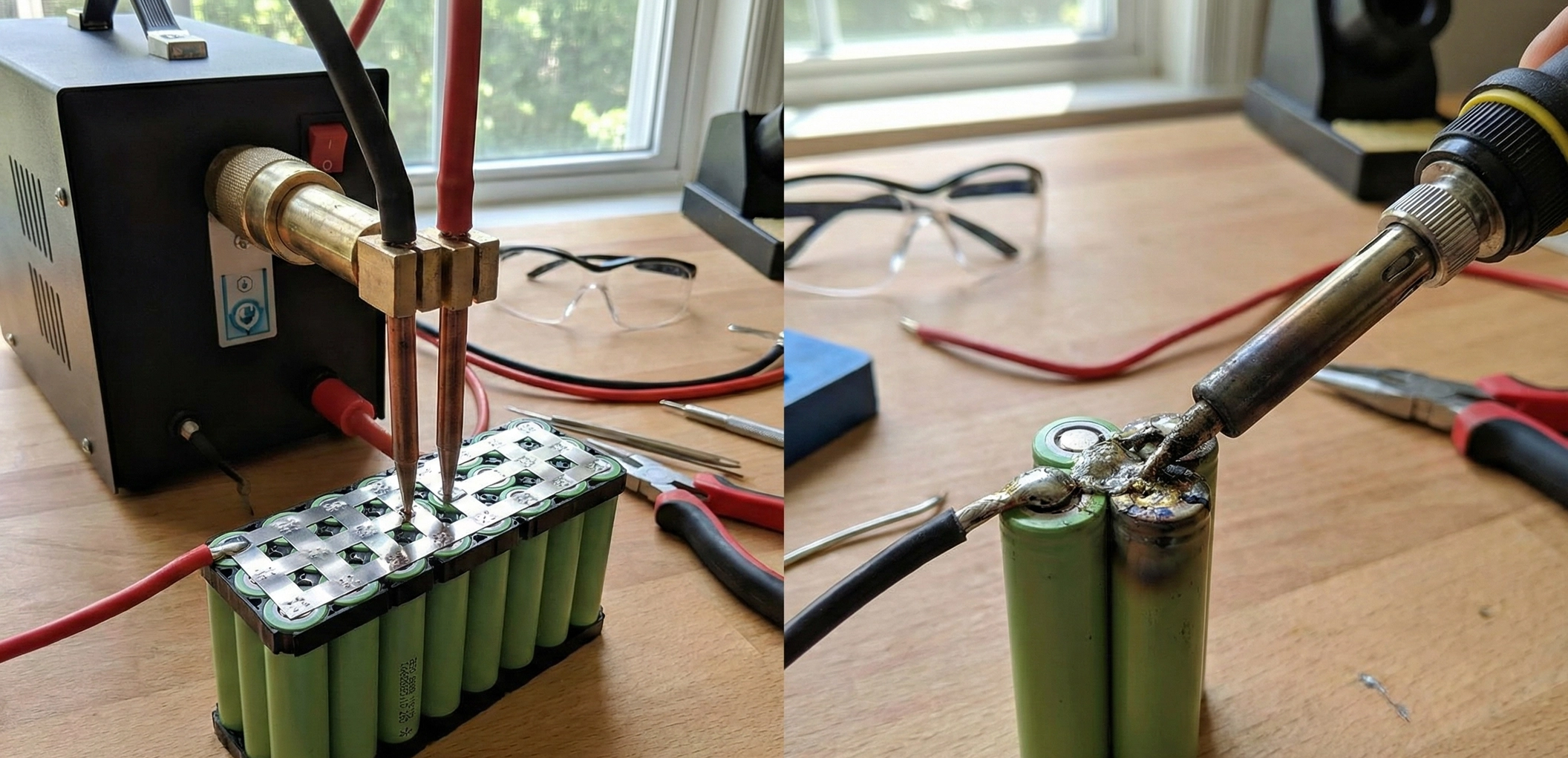

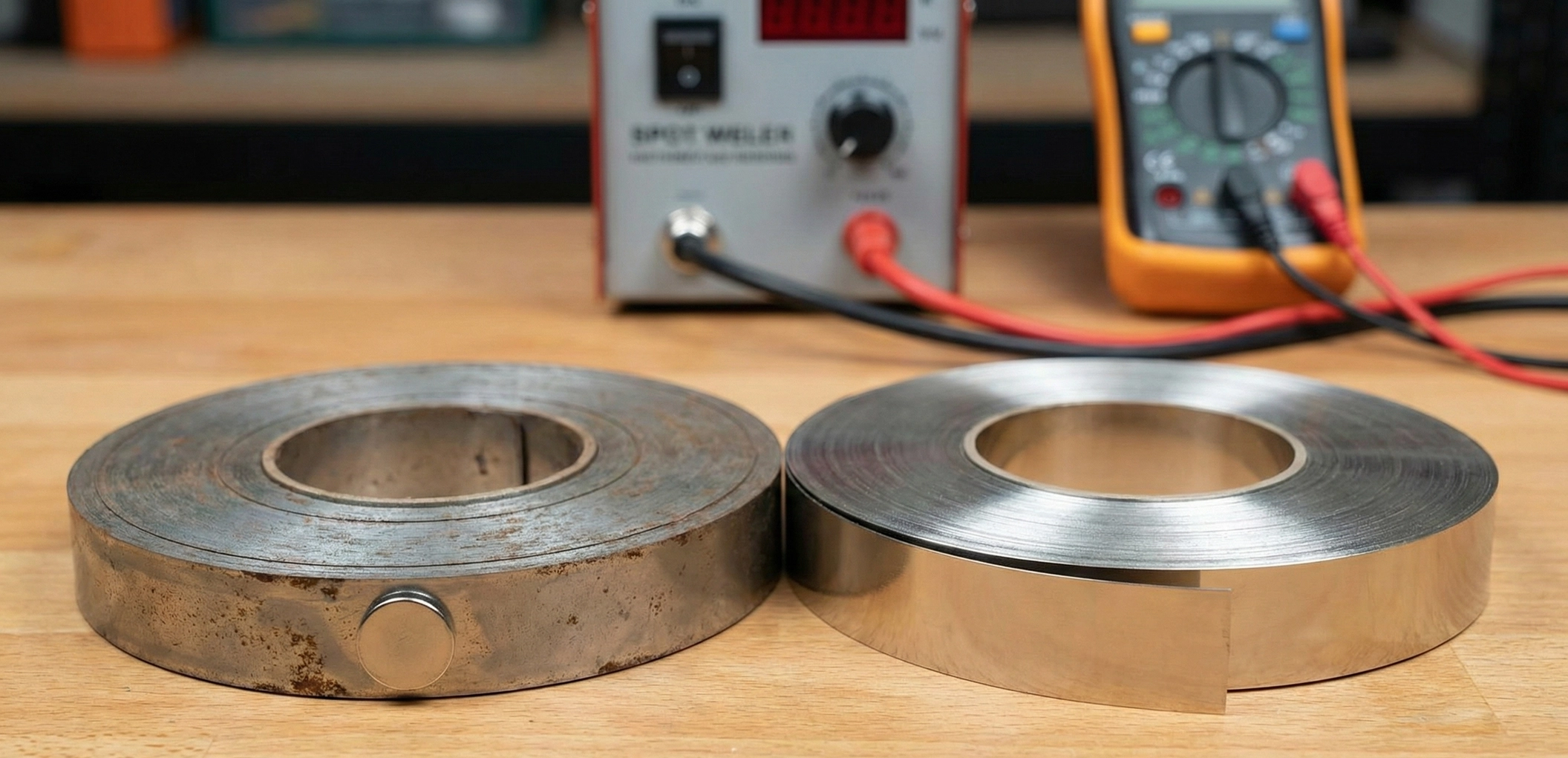

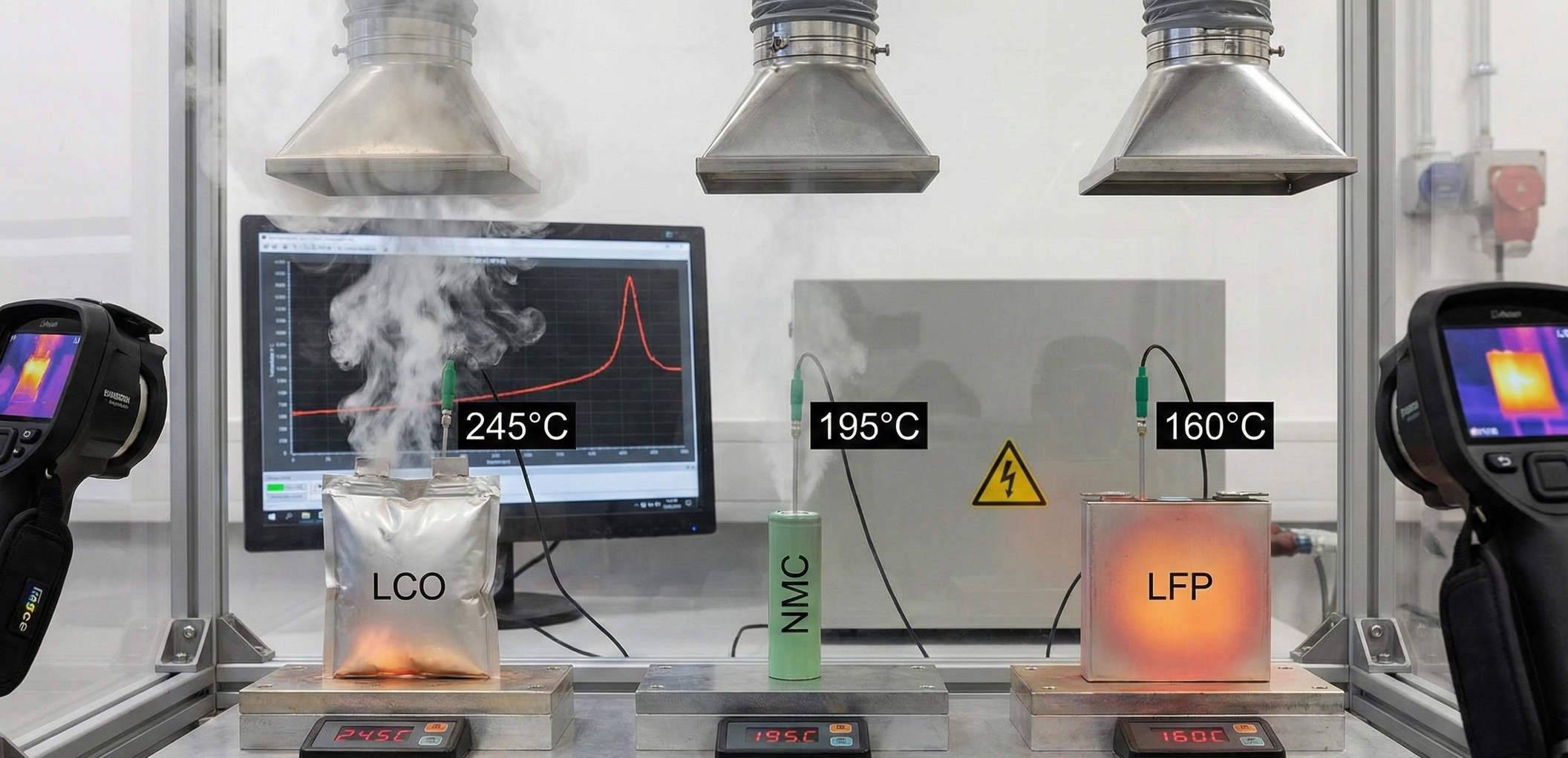

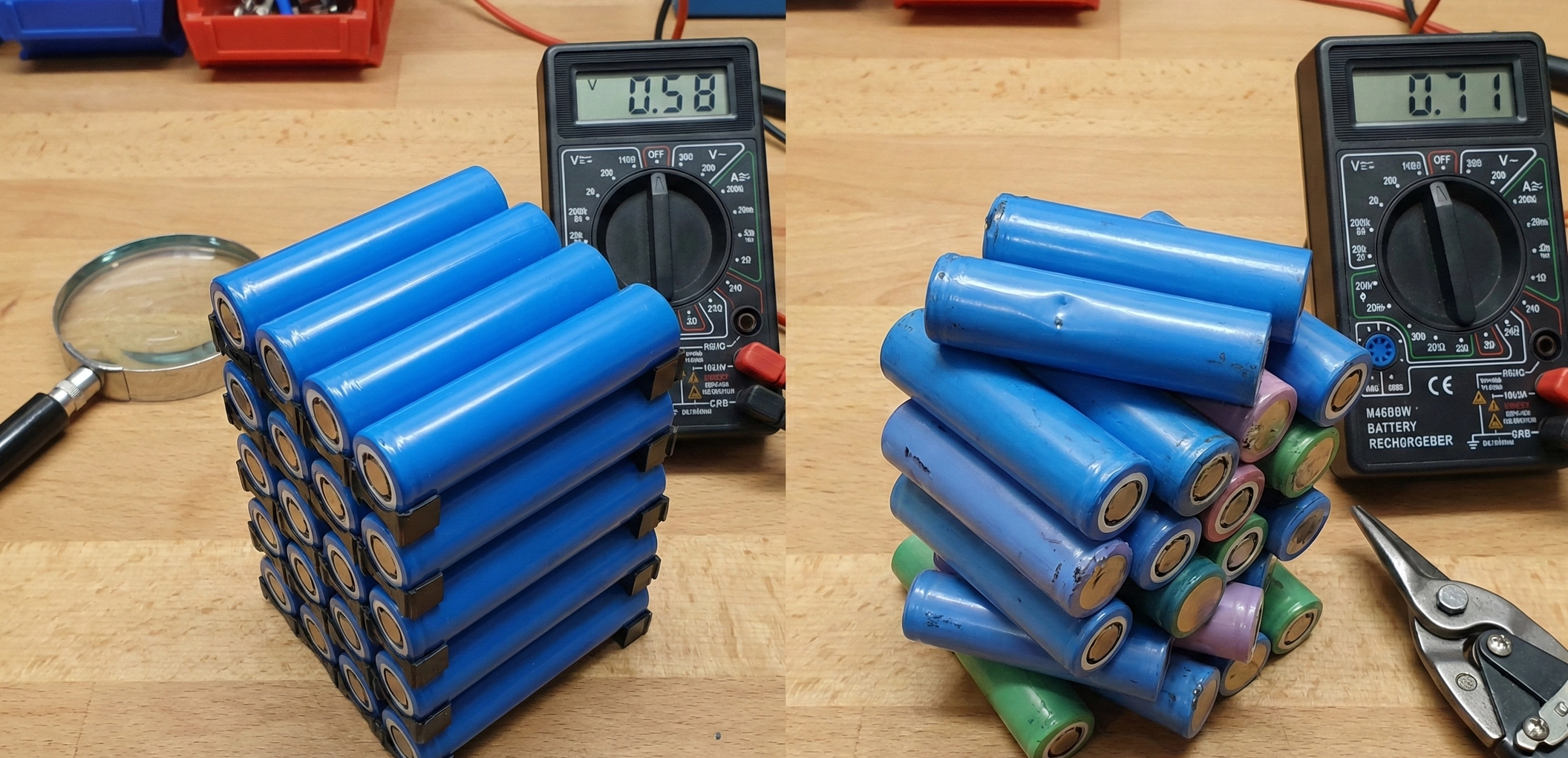

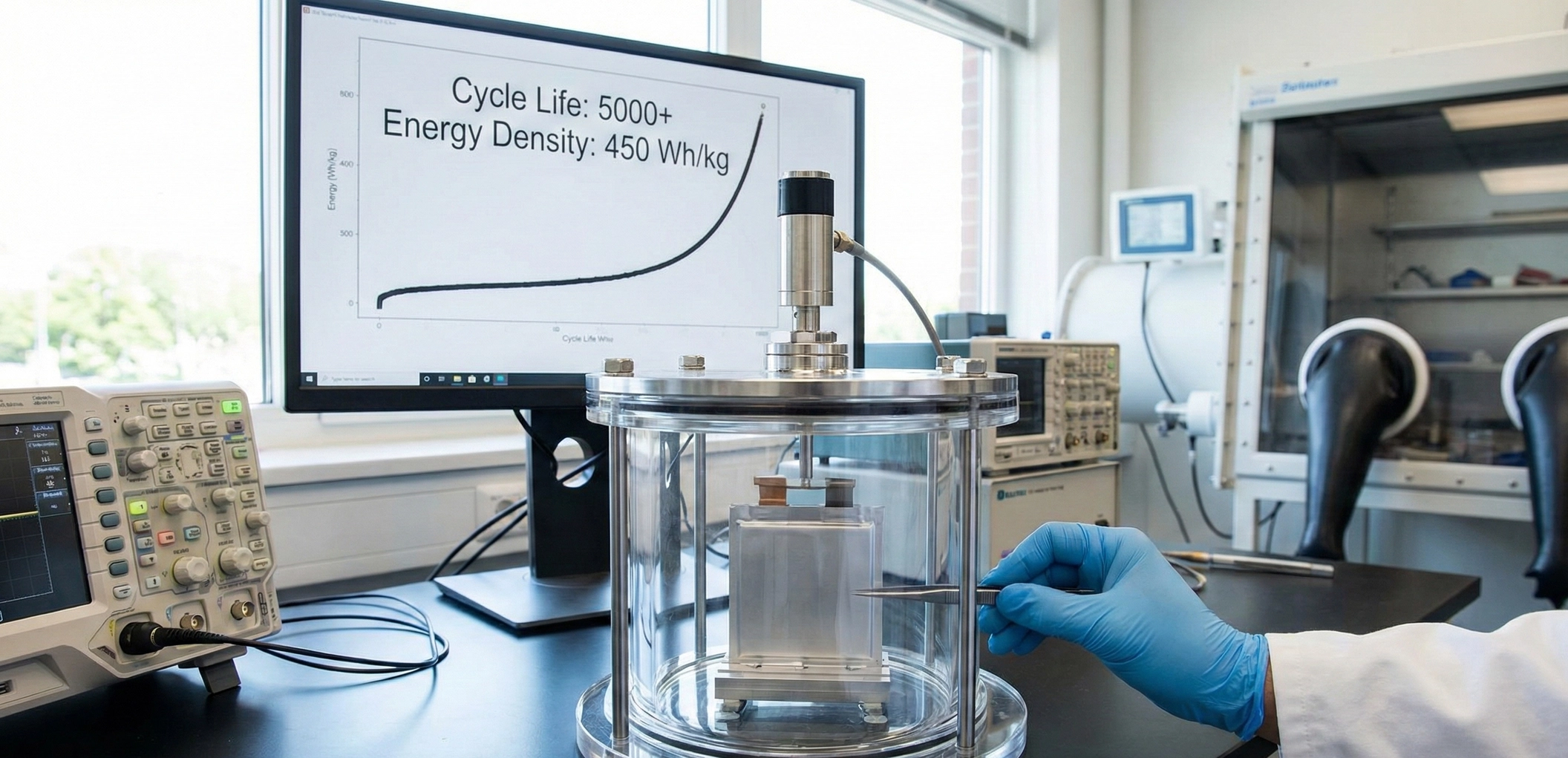

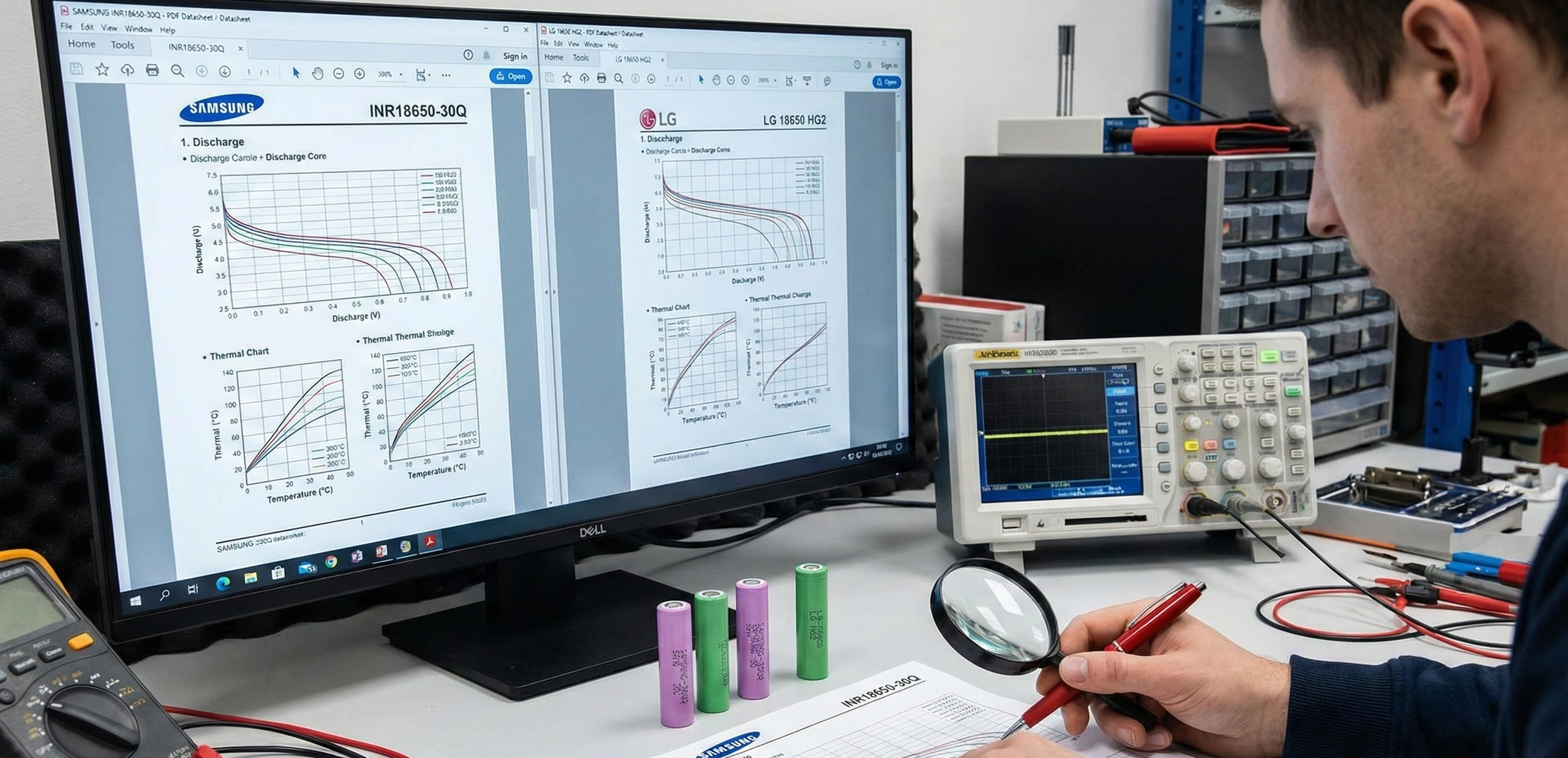

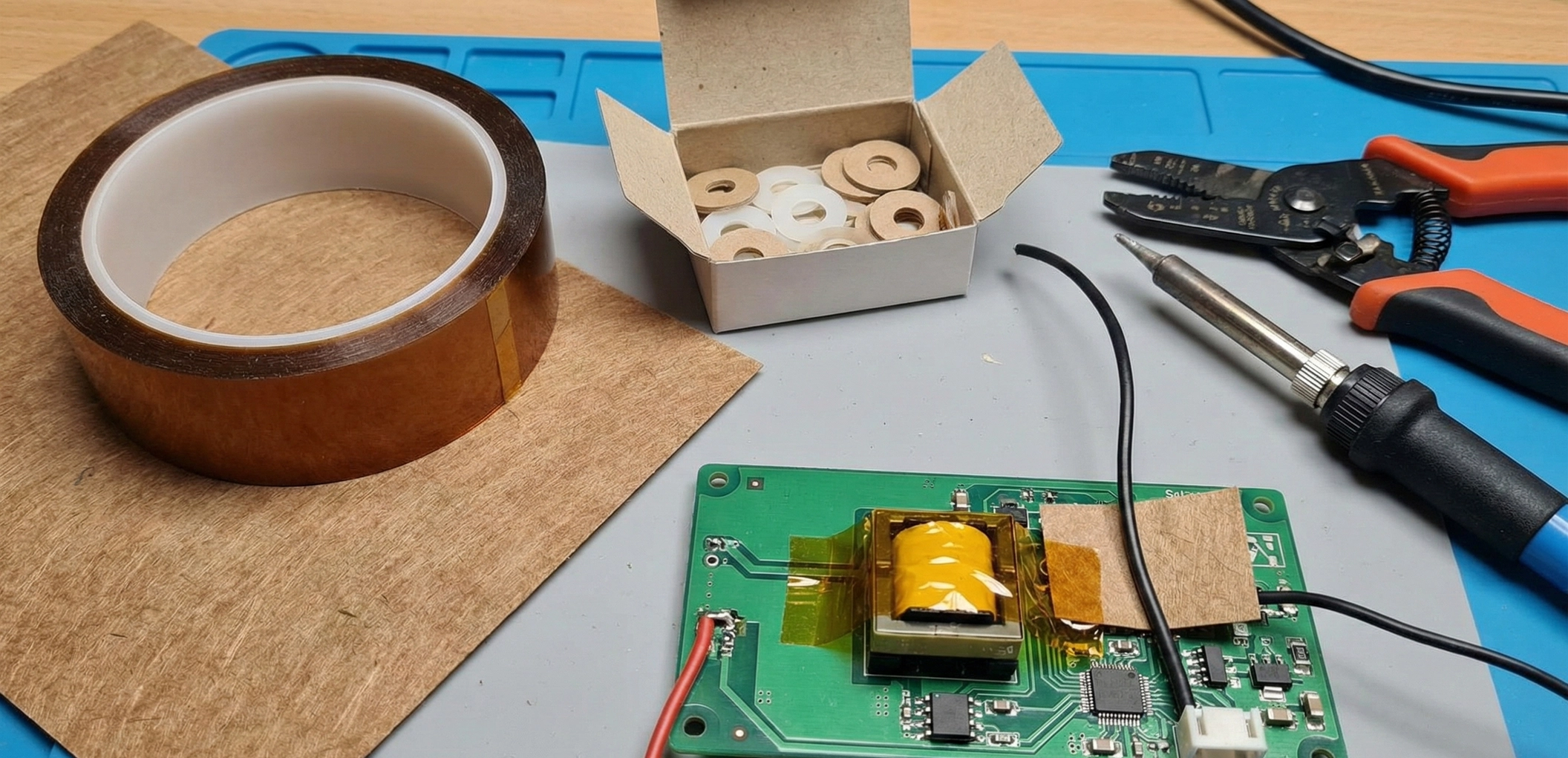

The Thin Line Between Power and PlasmaWhen you hold an 18650 cell in your hand, you are holding a potential bomb wrapped in a thin layer of plastic. Most beginners look at a battery and see a Positive top and a Negative bottom. This is a fatal oversimplification.The entire metal casing of a cylindrical cell—the sides, the bottom, and crucially, the curved "shoulder" right next to the positive button—is Negative. The only thing separating the Positive terminal from the Negative can at the top of the cell is a tiny, 0.2mm gap and a flimsy piece of heat-shrink PVC.This guide focuses on the single most critical safety step in battery assembly: Supplemental Insulation. If you skip this, vibration will eventually turn your battery into a flare.1. The "Guillotine" EffectWhy do packs fail after 6 months of riding? Vibration.When you spot weld a nickel strip to the positive terminal, that strip must travel across the top of the cell to connect to the next group. It lays directly over the "shoulder" of the cell—the sharp metal rim of the negative can.The Mechanism of Failure: 1. You weld the strip. It is tight against the cell top. 2. You ride your e-bike. The battery vibrates thousands of times a minute. 3. The sharp edge of the negative can (the shoulder) acts like a knife (a guillotine) rubbing against the underside of the nickel strip. 4. The only barrier is the cell's original PVC wrap. PVC is soft. It wears through. 5. BOOM. The nickel strip (Positive) touches the Can Edge (Negative). This is a dead short circuit with zero resistance. The nickel glows white-hot instantly, igniting the electrolyte.2. Material Science: Fishpaper (Vulcanized Fiber)To prevent the guillotine, you need a material that is tough, heat-resistant, and dielectric. Enter Fishpaper (also known as Barley Paper).What is it? It is a cotton-based paper that has been chemically treated (vulcanized) with zinc chloride. This process gelatinizes the cotton fibers, fusing them into a dense, non-laminated solid.Why use it? Unlike plastic tape, Fishpaper does not melt when you solder or spot weld near it. More importantly, it has incredible Abrasion Resistance. It is almost impossible for a dull metal edge to cut through it under vibration. It creates a physical shield over the negative shoulder of the cell.Mandatory Application: You MUST place a self-adhesive Fishpaper Ring (Insulator Ring) on the positive terminal of every single cell before spot welding. This adds a second, tougher layer of defense on top of the factory PVC.3. Material Science: Kapton Tape (Polyimide)You will see rolls of translucent yellow tape on every battery builder's bench. This is Polyimide tape, commonly referred to by the DuPont brand name "Kapton."Properties: - Heat Resistance: Withstands 400°C. You can solder right through it without it melting. - Dielectric Strength: Extremely high voltage insulation per micrometer. - Thinness: Usually only 0.05mm thick.The Trap: Kapton is amazing at stopping electricity and heat, but it is mechanically weak against puncture. A sharp point will poke right through it. Do NOT use Kapton to prevent the Guillotine Effect. The cell shoulder will slice through Kapton easily. Use Kapton to hold wires in place, to wrap the final pack, or to insulate flat surfaces. Use Fishpaper for sharp edges.4. The Layered Defense StrategyA professional pack uses insulation in specific layers:Layer 1: The RingApply a Fishpaper ring to every cell Positive terminal. This is non-negotiable. If you buy Recycled Cells, the original PVC is likely damaged, making this ring even more vital.Layer 2: Series Crossing ShieldsIn a 10S or 13S battery, the nickel strips carry increasingly different voltages. If a nickel strip from Group 1 (3.6V) crosses over Group 5 (18V), and they touch, you have a short. Wherever a series connection crosses a cell or another strip, place a rectangular strip of Fishpaper underneath the nickel to act as a bridge.Layer 3: Group IsolationIf you are folding your battery (e.g., gluing two rows back-to-back to make it thicker), you must put a full sheet of Fishpaper or thin Fiberglass sheet between the groups. Relying on the cell shrink wrap to separate 40V potential differences is gambling. Friction will eventually wear the PVC down.Layer 4: Final WrapBefore putting the blue PVC heat shrink on the whole pack, wrap the entire assembly in a layer of Fishpaper or thick fiber tape. This protects the BMS sense wires and main discharge cables from rubbing against the sharp edges of the nickel strips on the outside of the pack.5. Liquid Electrical Tape and SiliconesCan you use liquid insulation? Liquid Electrical Tape: Good for waterproofing lug crimps, but useless for mechanical protection inside a battery. It rubs off too easily. RTV Silicone: Excellent for potting and vibration dampening. Use Neutral Cure silicone to glue cells into holders or to secure heavy wires so they don't wiggle. Preventing movement is a form of insulation because if it can't move, it can't rub.6. The "Spark" Test (Don't do it)Some people think, "I'll just be careful." Try this mental exercise: Imagine your battery is in a paint shaker for 5 years. That is what an e-bike battery experiences on the road. "Careful" assembly doesn't stop physics. Abrasion is inevitable. If you disassemble a 3-year-old commercial battery (like a Bosch or Shimano), you will see plastic cages, paper separators, and silicone potting everywhere. They don't rely on luck. They rely on physical separation.Summary for the BuilderInsulation is cheap. A sheet of Fishpaper costs $1. A roll of Kapton costs $5. A battery fire costs your home. Rule of Thumb: If metal crosses metal, put paper between them. If metal touches a cell edge, put a ring on it. Never trust PVC shrink wrap to save your life.