Troubleshooting & Maintenance

Troubleshooting & Maintenance

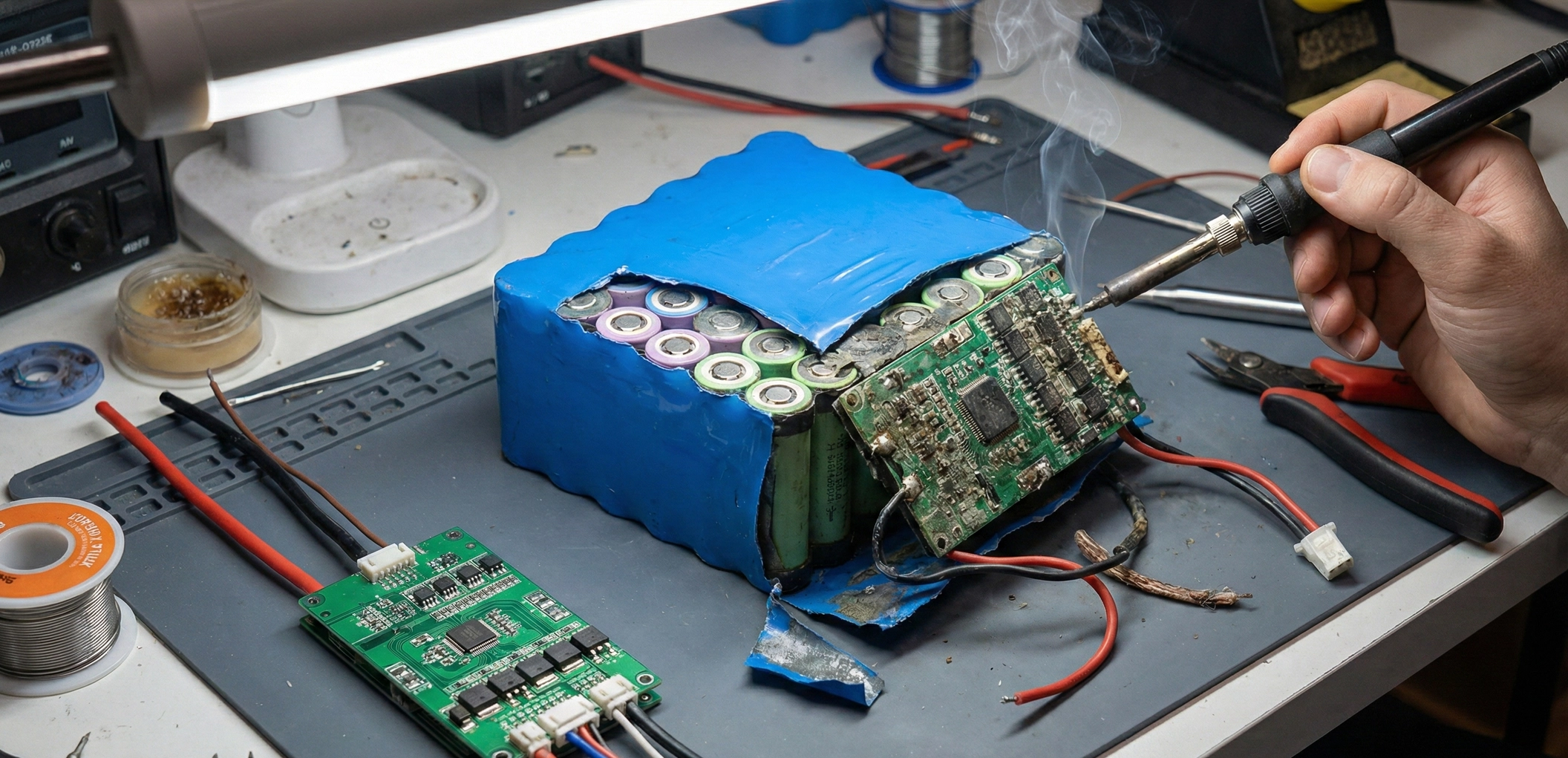

Replacing a BMS in an Existing Pack

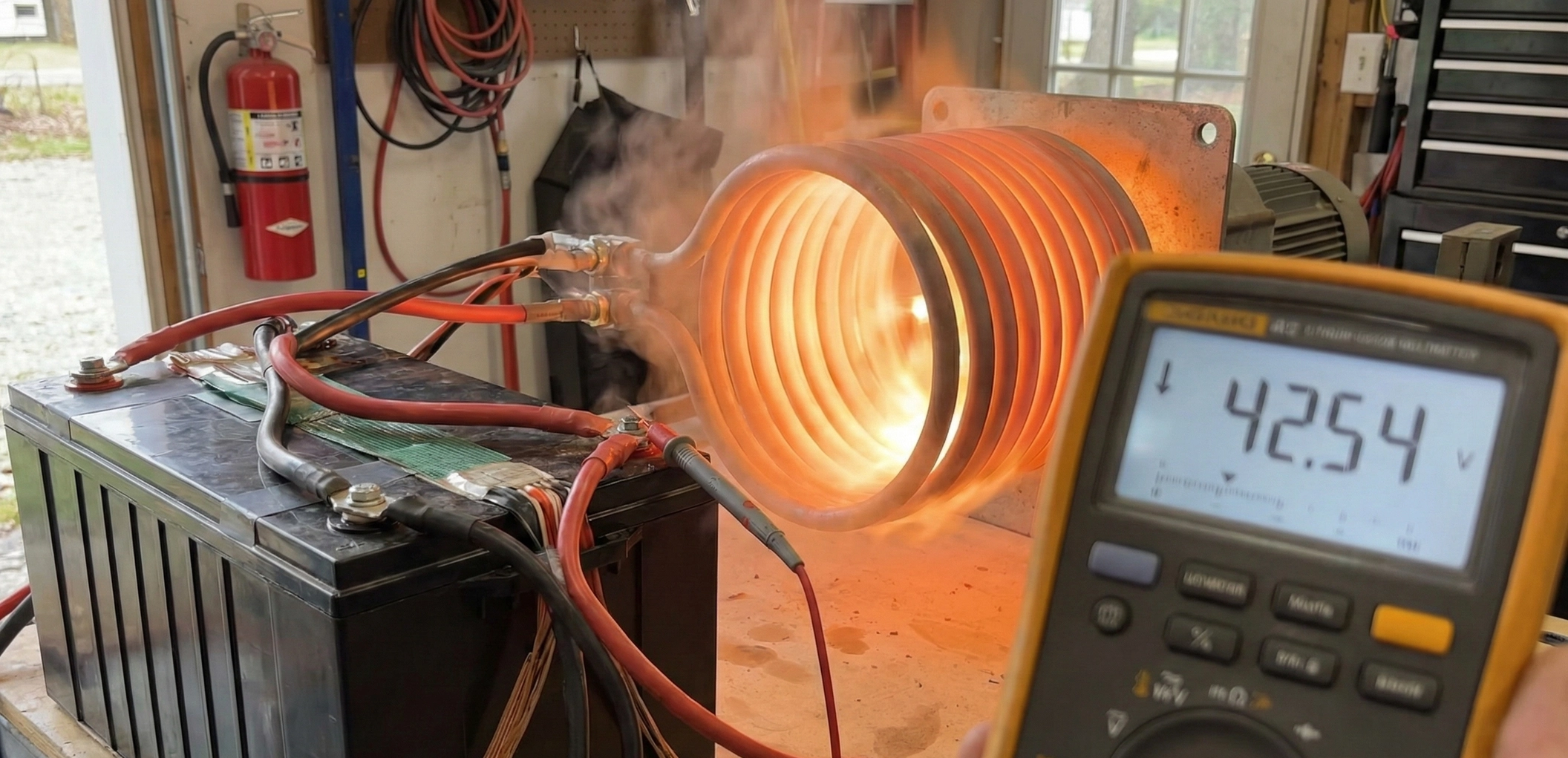

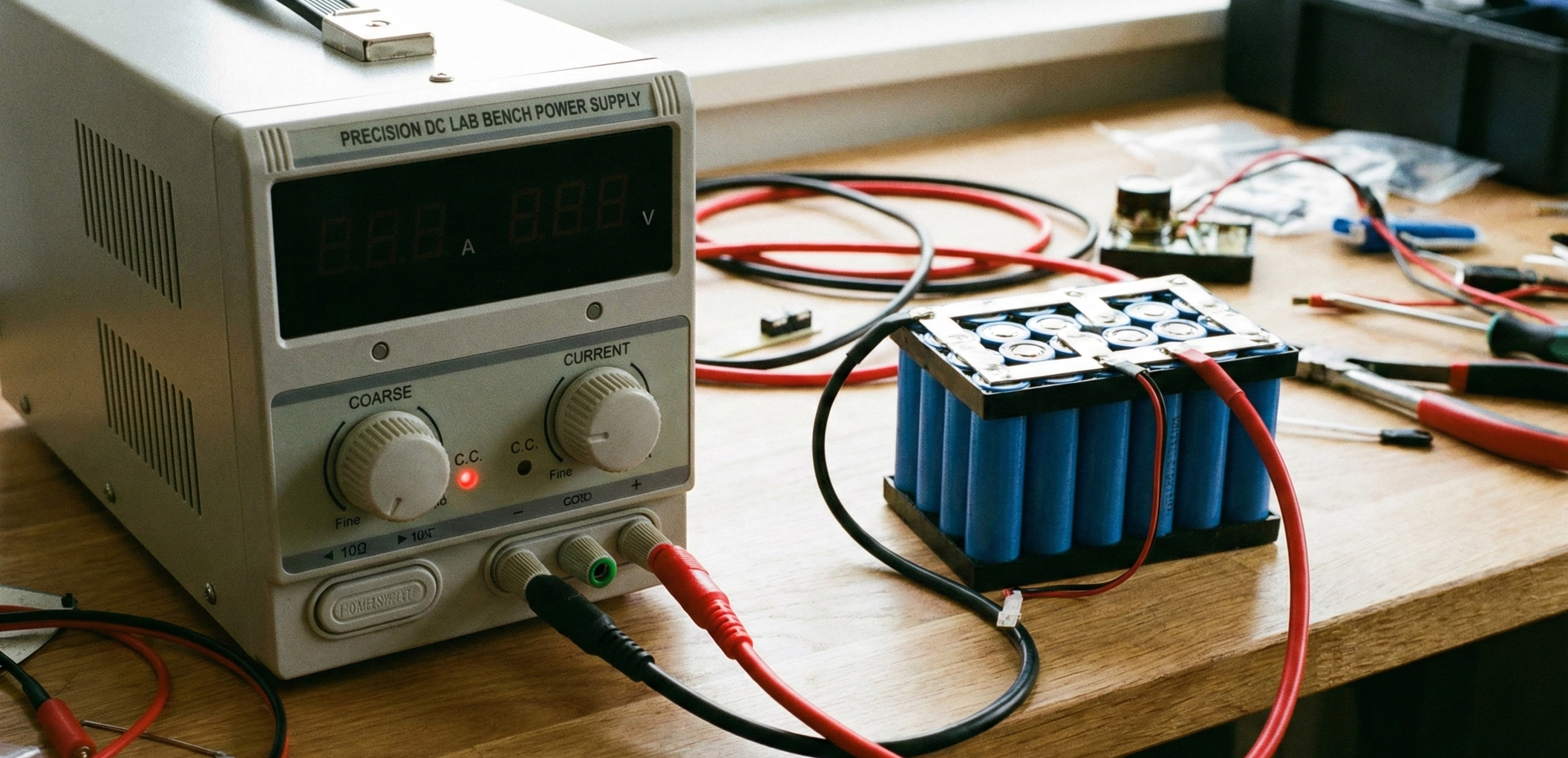

The High-Stakes RepairYou have verified your battery cells are balanced and healthy, but the output is dead. Your diagnosis points to a failed Battery Management System (BMS). Maybe a MOSFET failed closed, or a balance channel burnt out. You order a replacement.Replacing a BMS is fundamentally different from building a new battery. When building new, you connect the BMS before the series connections are live. When repairing, the battery is fully energized, sitting at 48V or 72V, waiting for a single slip of the screwdriver to arc-weld itself to your hand. This process is akin to performing open-heart surgery while the patient is awake and running a marathon. There is no "Off" switch. Strict adherence to the Order of Operations is the only thing keeping you safe.1. The Disconnection Protocol (Removal)You cannot just start cutting wires. The BMS relies on a specific ground reference to keep its logic logic gates stable. If you remove the main ground while the sense wires are still connected, the full pack voltage might try to find a path to ground through the thin balance wires, instantly frying the old BMS (if it wasn't dead already) and potentially damaging the cells.Step 1: Disconnect the Load/Charger (P-) Unbolt or desolder the thick blue or black wire going to the discharge connector. Tape the end of this wire immediately. It is now electrically floating, but we treat it as live.Step 2: Unplug the Balance Connector (CRITICAL) This is the most common mistake. Remove the white JST connector with the thin wires first. Do not cut the wires yet. Just unplug the harness from the BMS board. Why? This isolates the BMS logic from the high-voltage series taps. Once this is unplugged, the BMS is "blind."Step 3: Disconnect the Main Negative (B-) Now you can safely desolder or unbolt the thick black wire connecting the BMS to the Battery Main Negative. Once this is removed, the BMS is physically separated from the pack.2. Preparing the PatientWith the old BMS gone, you have a live battery with exposed terminals. Insulation Strategy: Use Kapton Tape or cardboard to cover every exposed nickel strip and terminal except the specific one you are working on. The B- Wire: Inspect the solder joint on the battery Main Negative. Is it cold? Is the wire frayed? Now is the time to fix it. Ideally, solder a new, high-quality silicone wire for the new BMS B- lead.3. The Pinout Trap: Never Trust the PlugYou bought a "Daly 13S BMS" to replace your old "Daly 13S BMS." The white connector looks identical. Can you just plug the old harness into the new BMS? ABSOLUTELY NOT.Manufacturers change pinouts constantly. - Old BMS: Pin 1 = Negative, Pin 2 = Cell 1... - New BMS: Pin 1 = Empty, Pin 2 = Negative... If you plug the old harness into the new BMS without checking, you will send 48V into a pin expecting 3V. The BMS will pop, smoke, and die instantly.Verification Procedure: 1. Take the new harness that came with the new BMS. 2. Compare it visually to the old harness. 3. Ideally, replace the harness entirely. Solder the new wires one by one to the cell groups. 4. If you must reuse the old harness, use a multimeter to verify every single pin against the new BMS wiring diagram before plugging it in.4. The Connection Protocol (Installation)This is the reverse of removal, but even more strict. (See our BMS Wiring Order guide for the physics).Step 1: Connect Main Negative (B-) Solder the thick B- wire from the BMS to the Battery Negative. Check: Tug on the wire. It must be solid. This is the ground reference for the logic.Step 2: Verify the Harness Voltages Before plugging in the white connector, put your multimeter black probe on the B- solder joint. Use the red probe to check each pin on the connector. Pin 1: 3.6V Pin 2: 7.2V ... Pin 13: 46.8V If the sequence is not perfect, STOP. Fix the wiring.Step 3: Plug in the Balance Connector Insert the plug firmly. You might see a tiny spark inside the connector. This is normal (capacitors charging).Step 4: Connect the Output (P-) Solder the discharge cable to the P- pad.5. Activation and TestingYour new BMS is installed, but the output voltage measures 0.0V. Did you kill it? No. Most new BMS units ship in "Shipment Mode" or "Protection Mode." They need a wake-up signal. How to Activate: Apply a charge voltage (from your e-bike charger) to the P- and P+ wires. As soon as current flows into the BMS, the logic resets, the MOSFETs open, and the battery goes live.Final Check: Measure the voltage at the actual cell terminals (e.g., 48.0V). Measure the voltage at the BMS output (P- to P+). They should be identical. If the output is 47.5V, you have a high-resistance connection or a bad FET.SummaryReplacing a BMS is a test of discipline. The temptation to "just plug it in" is high, but the cost of failure is a dead component or a shorted pack. By treating the battery as a live energetic device, taping off your work area, and triple-checking pinouts with a multimeter, you can perform this surgery safely and give your battery a second life.